The Crux of Pricing

Pricing becomes impossibly hard with the faintest whiff of uncertainty regarding your product’s differentiation. If you are unsure of the position your product holds, why it holds that unique spot, or what surrounds that position, it is hard to explain to buyers the value they receive for trading their dollars for your widget or service.

¶Pricing Is Hard

Even with well-formed boundaries, defining product positioning, and pricing new products can still vex seasoned executives.[1]

Departing from a commodities market requires differentiation; which is why pricing exercises always bring our positioning under the surgical lamp for examination. Mystical consultants can wax philosophical about strategy, dynamics, or other squishy concepts, but pricing is regimented and concrete, a visceral opposition to fluff, a stalwart of ink on a page. Pricing generates pride or embarrassment within the internal team because you it divides evenly the “bought-in” from the “doubters”. As an insider, you can not convince someone else of something you were unable to convince yourself of. See life principle #18:

“You can not impart what you do not possess” - Dewey Wilson

¶The Coffee Industry

Consider the case of the coffee farmer. For simplicity, lets say coffee has 5 categorical steps required to bring a complete product to market. 5 incredibly hard steps are required to get a “cup of joe” in front of a consumer for less than $5.[1]

- Coffee Farming

- Coffee Roasting

- Coffee Packaging

- Coffee Retailing

- Coffee Brewing/Making

One organization can do all or specialize in just one step of five. Bodum & Mr Coffee, for example, sell coffee grinders and drip coffee makers (at varied levels of perceived quality). Nesspresso and Keruig play in 3 areas: Packaging, Retailing, and Making. Central Market and Whole Foods operate in the selling and making (via in store coffee shops).

The coffee farmer aims to make beans different from any other coffee farmer. Coffee roaster, the next one down the chain, wants exclusive inputs, and to own an exclusive process. Thus with at least one of those exclusive inputs, they yield an exclusive product of their own as well. To package coffee, you want exclusive inputs plus a proprietary technology (usually aimed at longer periods of freshness). Coffee Retailing… the same pattern: exclusive inputs and a regional customer mind-share monopoly. Lastly, Starbucks has taught us the business of making coffee is all about exclusive inputs (coffee products) + a process to delight customers (yielding “an experience”)

Hopefully the pattern was not too painfully belabored.

No one wants to compete with the same inputs.

At no level of the value chain, does any player acquiesce they are basically the same as the other company. The extent of the coordination between companies to give up on “we are different” can define an industry.

When everyone gives up and competes with light visual cues and the hint of an idea of varied lifestyles as their brand you have the cut-throat textile industry. Avoid these industries. Consider Men’s shirts - namely: Polos, Tommy Hilfiger, Nautica, Hugo Boss, and Perry Ellis. They all start with the same inputs from Myanmar, you get different embroideries, different hidden labels, and slightly different prices. But largely the products are doomed for similarity and weak differentiation.

A more direct example would be a few Jeep dealerships around town. Their product is exaclty the same, thus they have to differentiate with services, experience, and geography. Notice I did not say they differentiate on price - there is only competition on price. The more you are different the less you are required to compete on price.

¶Commodities Compete on Price

If you make standards based on products. Like the steel manufacturing company churning out 2 inch “#10 bolts” with “24 turn” threads. This product is by definition similar with competing bolts - for the purpose of replacement and construction interfaces. Since any old bolt (of the right spec) SHOULD just fit, prices of bolts are driven down to incredibly low prices. Consider the manufacturing process of a bolt. Make molten steel, fill them in to molds, cool, and shave threads in at micro-meter precision, and ship this very heavy product around the world. It’s through the sheer wonder of modern economics and large volumes that any bolt cost less than $100. But that’s just a bolt. Most of us will never make or sell bolts.

¶Back to Coffee:

If you are making mass-production coffee, you tend to make average coffee if by no other reason than you start to define the average through your own sheer volume.

Volume is a necessity for certain buyers. Consider Folgers and Maxwell House: both look for volume producers at rock bottom prices. Since I have tried both recently - I would equate the two to the textile industry. Folgers and Maxwell House get similar inputs and create indiscernible outputs.

Now consider if Blue Bottle Coffee, Stumptown Coffee, or Intelligentsia come buying from your coffee farm. They care about how you are offering the best product that money can buy (Sure, they don’t want to spend a fortune, but if that is what is required - then it can be considered.)

This is a fundamental difference in buyers, and it is driven by an ability to articulate the difference in their coffee beans vs everyone else’s. For more reading: See the funny account of Kopi Luwak Coffee and the many counterfeiters. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kopi_Luwak)

Often “market feedback” is the refining pressure distilling your product and its communication to a desirable form. Without concrete feedback on: how are you different? why be different like that? how are you better? and “why should I care?”, we labor wearily in the sweltering fields of commodity pricing.

¶Priority 1 of any commodity is: Differentiation

In coffee beans, the proof is in the coffee. A green coffee bean represents an incomplete value chain. Coffee is not “coffee” until it is roasted (and usually sold). Thus coffee bean farmers look for customers (roasters) who care about exceptional inputs to their best process, which helps those roasters avoid the commodity market pricing whoas as well. Hence Rule number Uno of Commodity Pricing is:

Fight to not be a commodity[2]

¶NYC Office Space

Consider the office buildings in NYC. Sure you could go with a tier 3 office space for your new startup in NYC, however that does not help you say to the world that you have just raised your B round of funding. So you start looking at The Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, but the grand daddy of them all is the Flatiron building[3]. One of these iconic buildings helps signal to your customers that your firm has deep roots in NYC culture and is a NY based bellwether. You cannot put your company HQ anywhere. You don’t have every building to pick from, you have but a few.

So it goes for each real-estate developer who offers basically the same thing. Sheltered, air-conditioned, elevator-reachable floor space for office use. But each real estate project is carefully selected based on region and then the project is implemented to create a distinctive building that has no equal. In this way, they move from mere commodity to a “highly differentiated product.” As such, the floor-space rates at any of the buildings mentioned here do not go for average rates, instead commanding higher prices because of their unique place in NYC culture.[2]

¶The Ocean Between FREE and a Penny

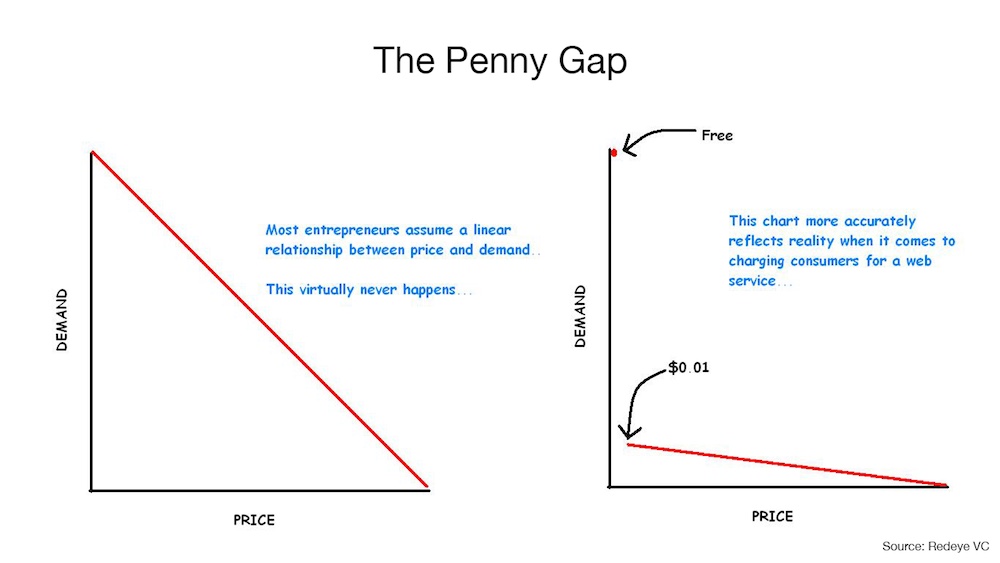

Additionally, don’t miss the well established principle of the “penny gap”. The chart above says two things in CAPSLOCK. 1) that entreprenuers think the demand curve is linear - it is not. It droops down like a string draped from the floor over a wall. 2) These types of systems have steep sides. Thus, the jump between free and one penny is always the steepest drop, but a very old post on the redeye VC notes this in a cheeky and approachable way.

Image Credits

fireskystudios.com McDobbie Hu

Reference: